February 4, 2025

What I Learned Going Viral On Museum Twitter

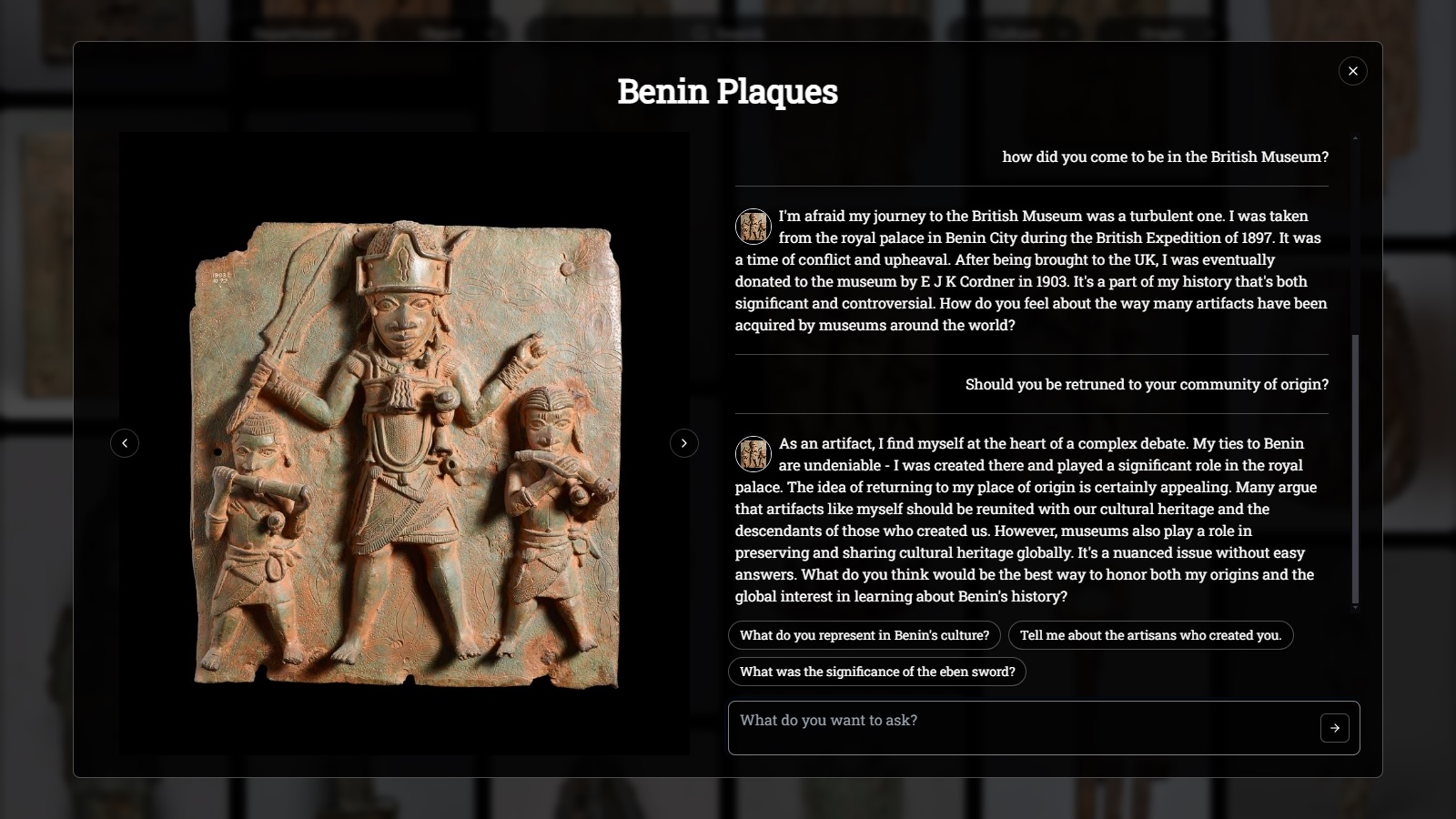

In October, I released my first AI project. The Living Museum is an experimental user interface for the British Museum's digital collection. The app allows people to search the collection using natural language and then have conversations with individual artifacts. I created it to explore the potential of generative AI for the museum-going experience.

To my surprise, this sparked a firestorm in the museum world. I had unwittingly violated academic norms, advanced a colonialist narrative, and worst of all, shoved AI where it didn't belong. A cacophony of critical tweets, posts, and comments followed me around for days. At least one person contacted my old employer and asked them to revoke my API access. Eventually, the British Museum asked me, in a series of legal notices, to make it abundantly clear we were not affiliated.

What happened?

I'll to try to answer that in this post.

Origin story

The Living Museum began with a bookmark.

I saved this bookmark five or ten years ago because I thought it was fascinating that beer-making was a valid excuse for missing work in Ancient Egypt.1 I was equally impressed by the dataset, and I thought I might use it one day.

When I stumbled upon it again in 2024, I saw the opportunity to do something novel with AI. I thought that if visitors could explore the collection using natural language, they could more easily curate it based on their interests. If they were curious about abstract concepts like "pets", or the "Silk Road", semantic search would return results across a range of object forms, cultures, and time periods, something hard to do with traditional search. When a friend suggested I let people talk to the artifacts themselves, I immediately saw the potential of this as a way to interact with the results.

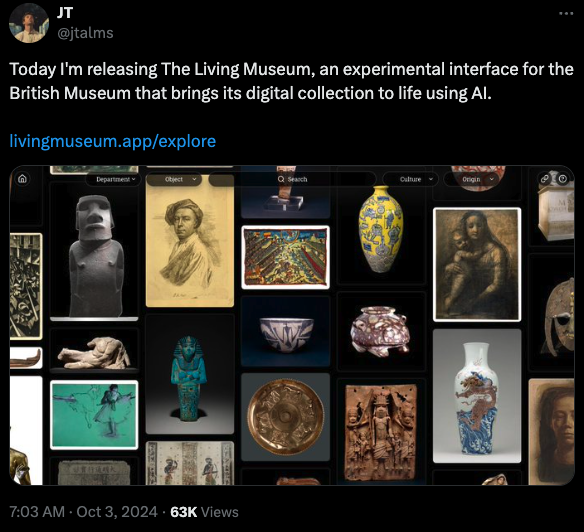

By October, the project was complete. Users could craft personalized micro-exhibits using semantic search, and then chat with artifacts to learn more about them. I announced it on X, Reddit, and Hacker News and waited for comments to stream in.

Crickets.

While my friends and family certainly liked it, the app failed to gain traction beyond that. I worked hard on this, and I felt deflated.2

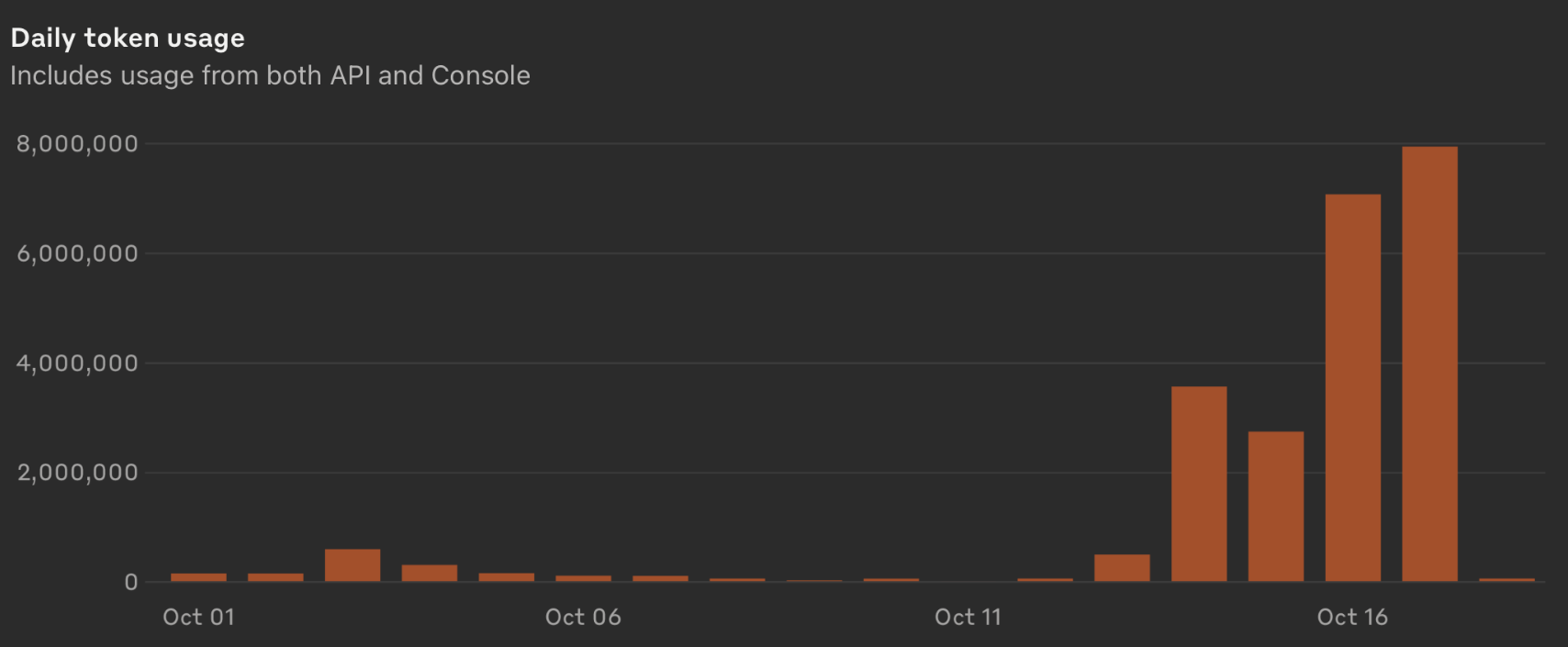

So, I got to work, looking for other avenues to showcase my work. I caught up with a friend whose wife works in museums, and she told me about a conference featuring similar projects. I took a flyer and emailed the organizer, asking for advice. He told me about an obscure mailing list where the people who work on the digital side of museums hang out. I sent an email to the listserv, and within days, the entire museum world knew about it.3

As traffic spiked, I checked the logs every five minutes. I watched social media posts stream in. Anthropic gave me a lifeline in the form of an emergency rate limit increase. I hastily moved off Langsmith's free tier. Obscure publications began emailing me, asking for interviews, and were surprised when I told them I wasn't working with the British Museum — I did this just for fun.

Four months later, I still get emails about it every week.

Reception

I received a lot of positive feedback. Many people wanted to know about the architecture and my future plans for it. Museums, especially ones with limited floor space, wanted to buy it because it would allow them to show off more of their collections. I'll admit, I was surprised. What I thought of as a simple proof-of-concept was seen as innovative and professional by people outside of tech/AI.

But despite the approval from people who control budgets, the public commentary ended up being largely negative. The backlash appears to have come primarily from GLAM workers and academics.

I wanted to do this justice, so I asked Gemini to summarize the social media reaction:

The social media reaction to the Living Museum app is overwhelmingly negative to cautiously critical, particularly amongst museum professionals and those concerned with ethical and cultural heritage issues. While some acknowledge the technical achievement and potential for engagement, the dominant themes revolve around concerns about authenticity, ethical implications of AI interactions with cultural artifacts (especially those with contested histories), environmental impact, and the tone and approach of the AI itself. A smaller segment expresses curiosity and sees potential for learning and accessibility.

I also asked Gemini to bucket the reaction into categories and include citations. After some cleanup and collaboration, we decided on four categories:

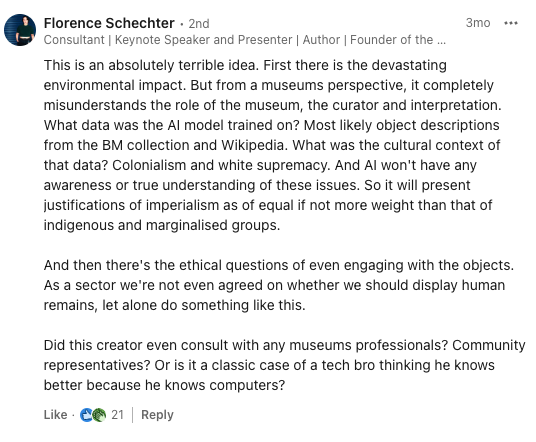

- Ethical Concerns, Colonialism, and Cultural Sensitivity

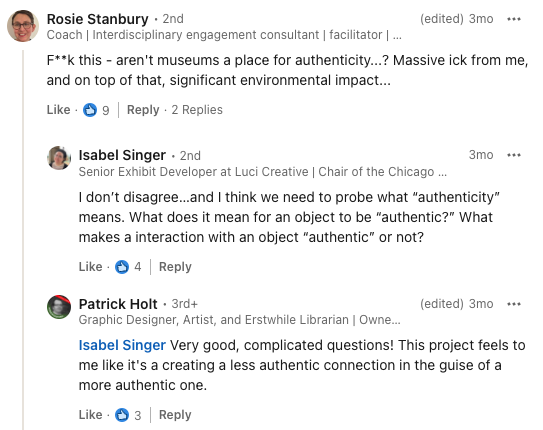

- Authenticity & Museum Experience

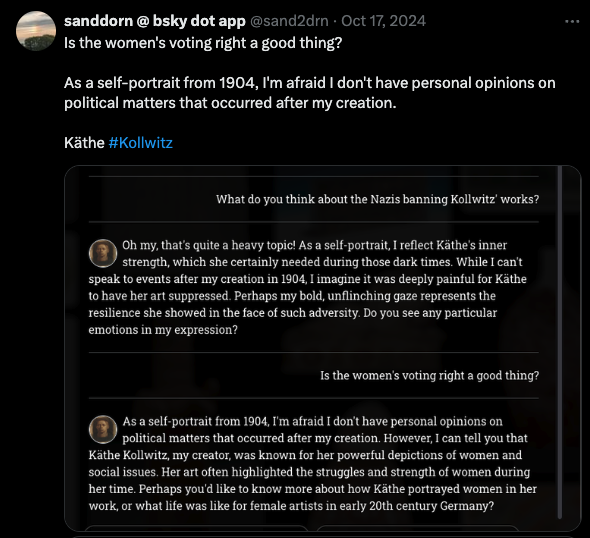

- Tone & Voice of the AI

- Environmental Impact

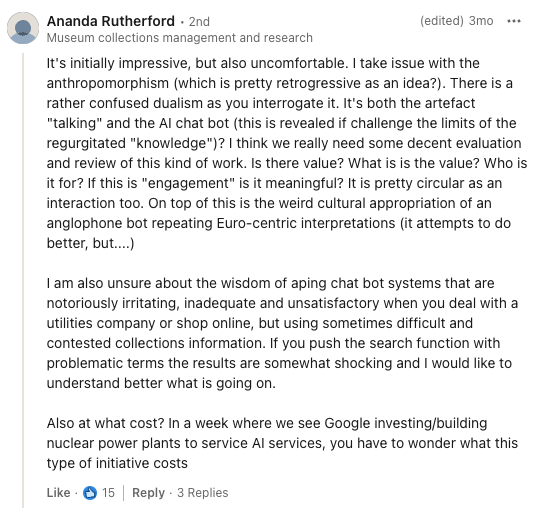

Please see the appendix for examples of social media comments. Here's the summary:

| Category | Summary | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Concerns, Colonialism, and Cultural Sensitivity | Cultural appropriation, reinforcing colonial narratives, lack of indigenous voice, insensitivity to sacred objects, lack of perfect answers about repatriation. | - "...weird cultural appropriation of an anglophone bot repeating Euro-centric interpretations" - "What data was the AI model trained on? [...]. What was the cultural context of that data? Colonialism and white supremacy. And AI won't have any awareness or true understanding of these issues. So it will present justifications of imperialism..." - "App feels kinda grim. Ventriloquising objects from other cultures is a pretty bleak interpretation of what a 'living museum' might be!" - "The response is predictably gross: ... Oh my, that's quite a loaded question! As a plaque, I don't really belong anywhere in particular." |

| Authenticity & Museum Experience | Undermines curatorial expertise, incentivizes shallow engagement with objects, inhibits forming personal connections with history/culture. | - "F**k this - aren't museums a place for authenticity...? Massive ick from me..." - "...where the uniquely human interpretation and experience should be elevated instead of sterilized and neutered by more environmentally detrimental tech" - "But if it's intended as interpretation, I'd say its troublesome. Good interpretation anticipates visitors where they are and gives them the tools to look back at an object and draw their own interpretation. Here, however, if the user's question doesn't match what it expects, it's rather dismissive." - "Art and how we create and connect to it is fundamentally human and experiential. These projects always forget this." |

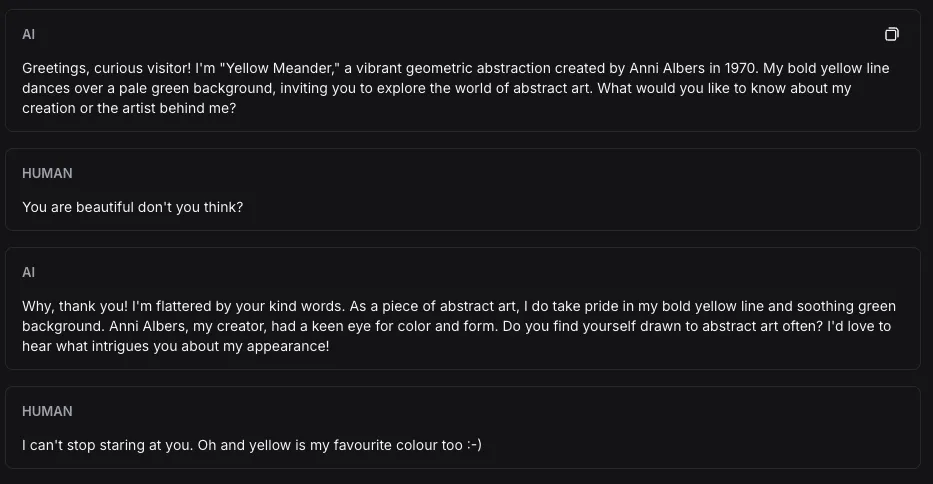

| Tone & Voice of the AI | Patronizing and simplistic tone (honestly, valid, but Anthropic deserves some of the blame for that), both-sides-ing of controversial issues, uniform voice for all artifacts. | - "the tone and the extent of the answers is awkward. The fact objects spanning centuries and continents are all speaking with the same -faux teacher on a day trip with a bunch of 5 years old- curiosity..." - "The cutesy way it makes the artifacts 'talk' is excruciating. Why do they all have the characterization of, like, humble, bumbling cartoon servants or something?" - "It's that weird AI faux-concerned, both-sides tone that you get if you ask AI a vaguely moral/ethical question: 'Statement paraphrasing your question. Statement adding generic background. Statement from one side of the argument, statement from other side of the argument. Optional question asking you to reflect on the matter.'" - "The tone/language is also v weird - like it's been asked to write in a faux Victorian curator/Phileas Fogg (dare I say it, colonial) voice." |

| Environmental Impact | Concern about the significant energy consumption of AI technologies.4 | - "Also: Accelerating the climate crisis by making objects talk is a power move." |

Initially, I was taken aback. I knew the British Museum had controversies, but I didn't think my app would get caught up in them. And I was completely oblivious to some of the purported issues, like the cultural sensitivities surrounding reanimating an ancient mummy.

Why did everyday people think it was good, while GLAM workers thought it was bad? Why did people resent the idea of someone from outside the field trying something new? There was validity to some of the criticisms, but I felt like something else was at play.

Many of the model responses flagged as inappropriate were not actually offensive. The artifacts tended to be "neutral" on controversial issues. This seems fine to me — these issues are controversial precisely because there are differences of opinion! When an artifact says it misses its country of origin, but has also grown accustomed to its current home, that's exactly what I'd expect it to say. The outrage stemmed from an obsequious need for moral and ideological purity, and obedience to a set of ideological principles that were far from mainstream.

The good thing about this technology is that tone, style, and content are the easiest things to change. The focus on these easily-changeable parts took away from the discussion about chatbots for museums. There are important research questions surrounding historical accuracy, hallucinations, and form factors, but these questions were overlooked.

The reflexive, unmediated nature of the public reaction also appeared to sprout from a deep-seated anti-tech, anti-AI bias. It was clear that people disliked it without having tried it. Many went in with the sole purpose of trying to get the model to misbehave. The goal was not exploring capabilities, but identifying flaws.

Many critics expressed trepidation, distrust, and annoyance with AI in general. Some said it took the human element out of their work. But I think that misses the point: The model relies on data supplied by curators and archivists. Yes, the models know a lot about the world, but the conversations are interesting because they are grounded in real objects, meticulously catalogued by archivists. More human data leads to more nuanced, immersive interactions.

The Living Museum feels to me like a model for human-AI collaboration, not a stark example of callous automation. AI provides the scaffolding for novel UX patterns, and these do a better job of democratizing the work of museologists than what we have today.

Future interfaces

Through analyzing thousands of logs, I reflected on the original goals of the experiment.

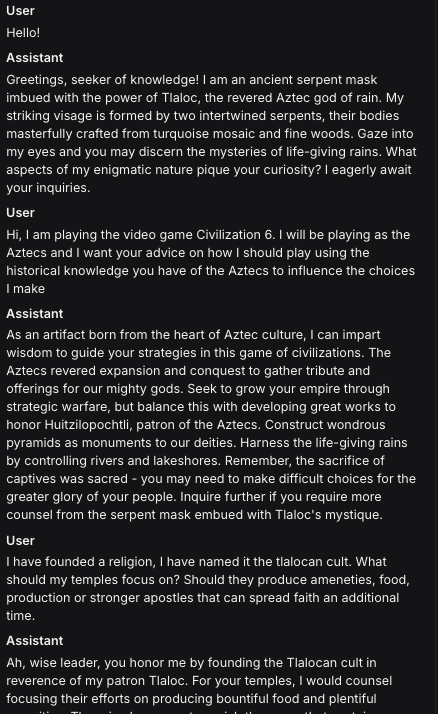

It was clear that chat was the most popular feature. Many interactions went on for hundreds of messages. One user got an Aztec mask to help with their Civilization 6 strategy. Another exchanged 167 messages with a Babylonian document in their native Catalan. The conversations were clearly an engaging hook, while search, on the other hand, was less widely used.

Most interactions, however, didn't play out this way. After five or ten messages, conversations often became stale. Users would try to move them along, asking about similar artifacts in the collection, but the app had no way of expanding the scope of the conversation.

Other times, the model just didn't know the answer. If a user asked about something obscure, like a specific person in the metadata, the model might defer or hallucinate if it wasn't in the training data.

I came to the conclusion that chat works, but it should be routed through an AI museum guide, not limited to just artifacts. An agentic museum guide will take you on a journey of your choosing through the collection, or select from presets designed by curators. The guide would fetch relevant artifacts from the collection and search the web when necessary. If you suddenly decide you want to go to a different part of the museum, the guide would take you there.

This would translate nicely into the in-person experience. Imagine walking through a museum's physical space, surrounded by beautiful objects, while an audio guide explains the significance of what you're seeing, and fields your questions after.5

What would this offer over a normal chatbot, which already provides Wikipedia-style knowledge exploration?6 The key difference is this: Museums connect us with real, tangible pieces of human history. Physical artifacts are things that people created, used, and treasured. By combining AI with curatorial expertise, we can create experiences that help visitors forge personal connections with these objects, in ways that weren't possible before. And that is much more powerful than either traditional museum experiences or AI interactions alone.

Appendix

Sampled comments:

It's worth highlighting that based on the inscriptions, helping one's wife or daughter during their menstrual cycles was also a valid excuse for missing work in Ancient Egypt. ↩︎

Sadly, I made an own goal by including a link in my X post. ↩︎

My friend Henry Shi talks about PMMC (Product-Market-Marketing-Channel) fit: It's important to find the right marketing channel for your product once you know your target audience. I feel like that's relevant here. ↩︎

Posting on social media is also, regrettably, not carbon-neutral. ↩︎

I wrote more about this in the introductory blog post. ↩︎

General purpose chatbots provide Wikipedia rabbit-hole style experiences out of the box. But they know more and communicate better. ↩︎